By Liz Schafer

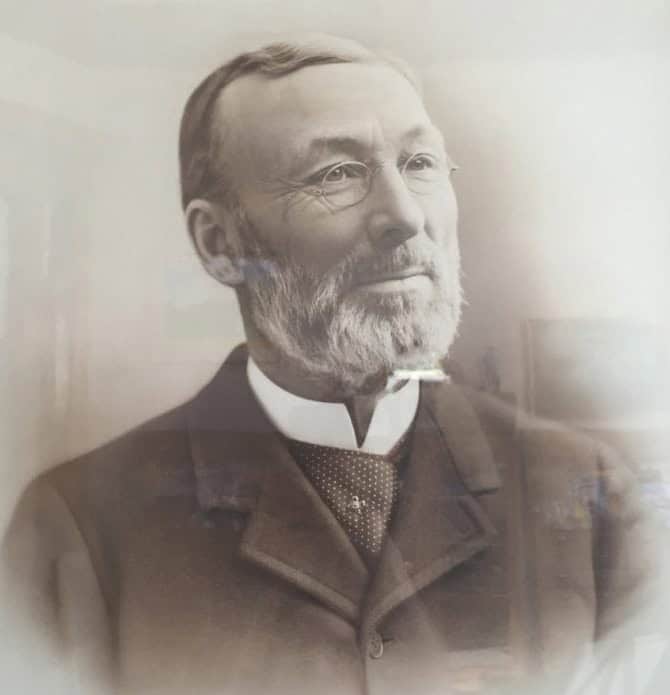

Was Vermont’s first millionaire a greedy curmudgeon, bent on profit at any cost, or a generous benefactor whose legacy continues to serve his hometown? That depends on who you ask. But no one can dispute that Silas Lapham Griffith—landowner, politician, business mogul—was a brilliant man who made significant contributions to the growth and prosperity of early southern Vermont.

Thwarted by Circumstance

Born in 1837, Griffith grew up working alongside his father and two brothers on their family farm in Danby. At sixteen, he left the farm to work as a store clerk, saving his income for two years so he could attend college in New Hampshire. However, his ambitions fell through; after paying for tuition, he had little cash left for heat and food. After a winter of privation, he was forced to return home. Shortly thereafter, he accepted a teaching position to the west. He undertook the journey by train, with plans to stop and visit relatives in Buffalo, New York. Once again, he was thwarted, this time by a wretched coincidence—a stretch of severe winter weather which came to be known as the Great Freeze (when brutal cold, wind and heavy snow brought transportation to a halt), and the financial Panic of 1857, which rendered his money useless. (The early 1850s had been prosperous because gold was plentiful, and many businesses had made risky investments; when the gold harvest began to decline, thousands lost their livelihoods. Many banks did not recover completely until after the Civil War.) Silas once again retreated homeward.

From Last Resort to Wild Success

How he managed to recover from these early disappointments is a tale of grit, determination and inventiveness. Borrowing $1000 from an uncle, he opened his own general store just a year later, and within four years had become one of the most successful businessmen in town. Over time, Griffith’s interests expanded to include land and business interests in surrounding communities, including Dorset. His holdings included over 50,000 acres, supporting an extensive lumber and charcoal business that included a payroll of over 600 men, numerous oxen and horses, nine sawmills, 27 charcoal kilns, several repair shops, and six general stores—one of which, at three stories high, was at the time the tallest building in southern Vermont. He also established the first fish hatchery in Vermont, supplying the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City with fresh trout shipped by rail from Mount Tabor.

Griffith was a master of efficiency, finding ways to use the byproducts of his business to increase profits. He had workers use saws to cut down trees because axes created too much waste. He developed a spring-fed gravity water system to provide the town with water and to power steam mills that processed scrap wood into boxes and other useful items; he sold sawdust to ice houses; and he made charcoal from unmarketable wood, selling and shipping a million bushels each year to power factories throughout the northeast.

Rising Adversity & Personal Woes

Griffith’s insistence on productivity often put him at odds with the men who worked for him. They saw him as cheap and overly strict. He would not allow them to wear watches so they couldn’t know how long they worked. They were housed in villages surrounding his saw mills, and their meager incomes were spent for goods at one of his general stores–often on credit. Griffith seemed to view them as cogs in a wheel, without due regard for their wellbeing. The discrepancy between their lives and that of their employer was huge.

Griffith’s own home was a grand Victorian affair in Danby Village, with all of the era’s modern conveniences. His personal life, however, was not without its sorrows. He and his wife, Lottie Staples, lost three of their four children, and after 20 years of marriage, she filed for divorce; he’d had an affair with his secretary, and when things came to light, it cost him $30,000 in settlement fees, further eroding his local reputation. Now in his mid-40s, did Griffith feel the need to redeem himself by somehow burning bridges to the past?

A New Beginning

When he remarried in 1891 to Katherine Teil, he tore down his beautiful house, using the salvage to make charcoal, and built a new, even more lavish home, with extravagant architecture, stained glass windows and carved oak woodwork. There were also hothouses to grow flowers, overseen by a professional florist, which he did not operate as a business, but gave away to the sick and grieving, to the church, and to the hospital. Griffith also began supporting local charities and institutions, especially the Danby Congregational Church. He even went on to serve on the Vermont State Senate, and was encouraged by his peers to run for Governor of the State, an honor which he declined.

Instead, in 1898, Senator Griffith purchased a second fish hatchery in Groton Vermont, reputed to be the world’s largest, a wise investment at the time (local waterways had been overfished by a growing population of settlers.) By then, profits from his timber operations were declining, with thousands of acres denuded from years of harvest. Demand for charcoal fell as industries began to use coal instead. The communities that had built up around the sawmills dispersed, rendering the general stores inoperative. But Griffith was a very wealthy man, and his mind turned to travelling the county. He eventually bought a fruit ranch in southern California, where he lived until his death in 1903.

A Final Redemption

Griffith’s Vermont business empire died with him, but his legacy in southern Vermont lives on. His will assured that the Danby Congregational Church will forever be the beneficiary of a fund established so that the children in Danby and Mount Tabor receive toys and gifts each Christmas. His bequest further provided the funds to build, equip and perpetually fund the SL Griffith Memorial Library in Danby Village. Much of Griffith’s lands, now under the protection of the US Forest Service, are covered in second-growth forest. Physical traces of Griffith’s vast empire remain, if you know where to look: crumbled bricks, stone foundations, cellar holes, remnants of the fish hatchery. It’s a mixed legacy, appropriate for one of Vermont’s most influential, if complicated, characters.